Everything You Need to Know About User Behaviour

Many product teams fall into the "research trap" while trying to decode users. Learn how to save thousands on qualitative research by relying on heuristics instead of analysis paralysis.

About five years ago I have started a new role as a product leader for an emerging team. As of today, I remember sanctioning extensive qual research to understand how users are going to interact with the product page. Where are their focal points, drop-offs, and in general barriers preventing users from converting into buyers?

When we presented the findings to our peers and leadership during the Product All-Hands, there was modest curiosity all around. The thing is - we haven’t uncovered anything groundbreaking. At least nothing that I haven’t known before.

After our speech, my manager came to me and said “Well done, but I’ve hired a senior leader exactly to avoid such spent. With your expertise you should be able to make decisions based on shortcuts, not expensive research”. That phrase stuck with me to this day.

Of course, It shouldn’t be taken to an extreme and there are legit cases where the uncertainty and the blast mistake radius are high, justifying the investment in the qual studies. But as for most of the research that’s done in a typical product team, it can be greatly reduced.

The Research Trap

Based on my experience, many managers tend to look to academic research (guilty myself). But all academic studies should be treated with a grain of salt as their definition of success is almost always wildly different from a business one.

Estimating the causal relation between lateral forces and the rate of penetration of hammer drilling can be considered a success in the context of academia. But are those learnings easily transferrable to the business? In some extreme cases, academic research is overdone to an extreme by blasting regression models and ML when in a business world a simple correlation would suffice.

Reminiscing about my old days as a Ph.D. student, I’ve published around 11 scientific articles and a monography on the intersection of economics and statistics. During the numerous re-writings and iterations of those works, two key requirements were posed by my supervisors:

the object of research and its outputs need to have newness for the academic field of research;

work should be written in a language that is compliant with academic expectations.

Confessing now, I used layers of foggy academic language and non-sense mathematical theories to somehow prove my belonging to the scientific circle. If I were to open any of my past works today - they would be almost impossible to read without cognitive overload.

Of course, not all research is done similarly and there are some great exceptions. However, most of the whitepapers you can access online were written for somebody to advance in their academic career, not add value to your decision-making as a business.

The dangerous trap happens when a product manager tries to find ultimate answers in academic research studies or tends to dig as deep as academia does, losing sight of the forest behind the trees. Yes, the studies can provide some additional angles for a problem and insights but should be considered strictly supplementary and not role models for decision-making in product management.

On the surface, it seems that there’s so much that needs to be researched and we know so little about our users. Hence, we tend to invest thousands of euros and hours of time in a fruitless attempt to grasp the motivation behind user behavior. But after you spend that much effort, you might arrive at a surprising conclusion (as did I) that there are more commonalities than differences.

Let’s start with dispelling the biggest myths that fog the actual understanding of user behavior.

The biggest myths about users

Hyperlocal users

Back in the early 2010s era when having a separate app for every single use case was justified - the myth about hyperlocal users was born. The myth isn’t without reasoning: there’s cultural and economic diversity, leading to the versatility of use patterns. A single app or web service would be used differently across the globe. Activation and engagement in India would be completely different from the one in the US or Japan. Yes, it would, but for a set of very different reasons, not related directly to the usage patterns (we’re going to talk about them below).

At the time I had a vague notion about hyperlocal use since my focus was a single-market product. Then during one of the coffee breaks at the “Mind the Product” conference, I’ve gotten acquainted with a PM from Booking.com. The glass walls of my ignorance were shattered as it turned out they didn’t have hyperlocal extensions for their service. Bluntly speaking, Booking.com have offered a single website and an app to cater to all nationalities across the world. The same case was true for the mainstream services (Instragram, Facebook, Google Search) with a global presence.

The rationale behind it is pretty straightforward, you simply cannot scale if you don’t have a single uniform platform working across all your markets. Every new expansion would turn into a product and engineering maintenance nightmare. In practicality, this invites a generalization that all users across all cultural landscapes use similar products pretty much in the same way.

Of course, researching various facets of hyperlocal behavior is a fun and engaging exercise, which will lead to many learnings. However, I doubt that most of those learnings would have any practical use for your decision-making as a business.

The generation divide

There are just tons of research studies on the peculiarities of various generational groups. The viral aspect can be easily explained as the generational split is a catchy framework to think about the demands and traits of various age groups. Boomers are anxious about their future prospects and healthcare, millennials tend to shape experiences in their lives while the youngest Gen-Z/Alpha are mindlessly consuming content over TikTok.

Our willingness to look at the world through the generational lens was very succinctly noted by a researcher and professor Bobby Duffy:

“Our primary way of understanding generations, through superficial and poor-quality punditry, manufactures a multitude of generational differences. Although these fake differences may individually seem trivial and sometimes even funny, there are so many that they can infect the opinions and actions of even sensible skeptics.”

The Generation Myth

Bobby Duffy

Back in my OLX days, I’ve fallen for it myself and pushed for a massive two-month research on Gen-Z content consumption and shopping behaviors. After days of brainstorming and qual interviews, we uncovered a few peculiarities:

The younger generation is more akin to kick-off a conversational chat with support rather than engaging in lengthy email threads;

Z-tters never use hashtags for navigation;

Z-tters have little prejudices of ownership and are open to a shared economy.

When it came to actual prototype testing, we observed that the sole distinction between the younger and older generations was their level of proficiency in app/web use. A kid born with an iPhone in his hand is much more skilled in jumping between contexts and content than an average boomer, who struggles to understand the interface complexities. However, this doesn’t mean that a boomer grandma is going to consume endless scroll content differently from a 15-year-old kid - the patterns are going to be really similar, just at a different speed.

Perception of time and space

Back in 2016, I was visiting a “Product Management Festival” conference in Zurich. One keynote particularly struck me. It was a product design talk on the perception of time and space by various cultures and how it can impact our app design patterns.

European cultures perceive time as going from left to right (similar to the reading pattern), Arabic cultures vice-versa while Asian and Chinese cultures in particular discern time as something that flows from top to bottom (as hieroglyphs do).

The research was done in Google Labs and seemed inspiring at the time. However, since then I haven’t seen a single visible application of those learnings. Later on, I stumbled upon a few mind-expanding studies on temporal diversity (e.g. cross-cultural perspectives of time). Although, I do tend to agree with the well-backed claims about how culture shapes our perception of the current time, past, and future - it doesn’t directly carry over to the use of the interfaces.

What’s the difference then?

If there are so many similarities in the usage patterns between consumers across the globe - then what are the key differences?

There are plenty, but on a conceptual level there are five major differences:

Perception of the value prop

The value proposition is relative and contextual, hence, different user segments would react to it differently.

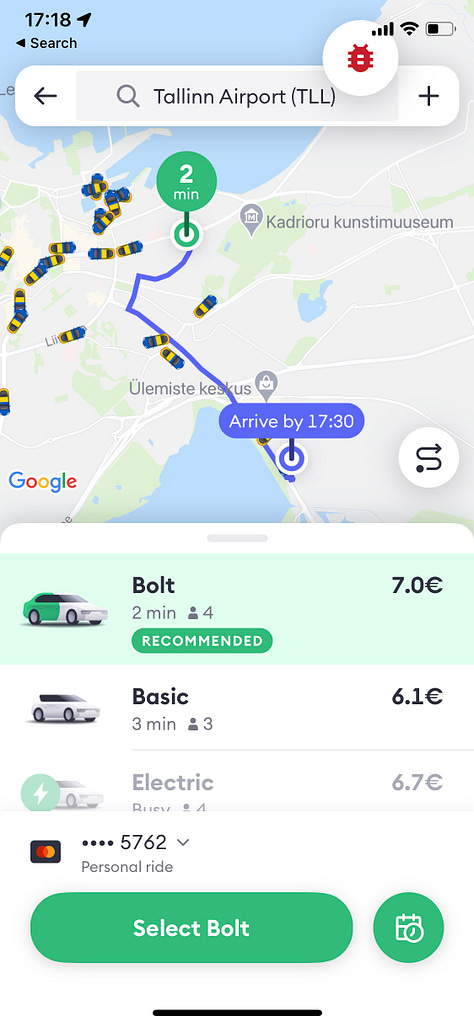

Payments and trust

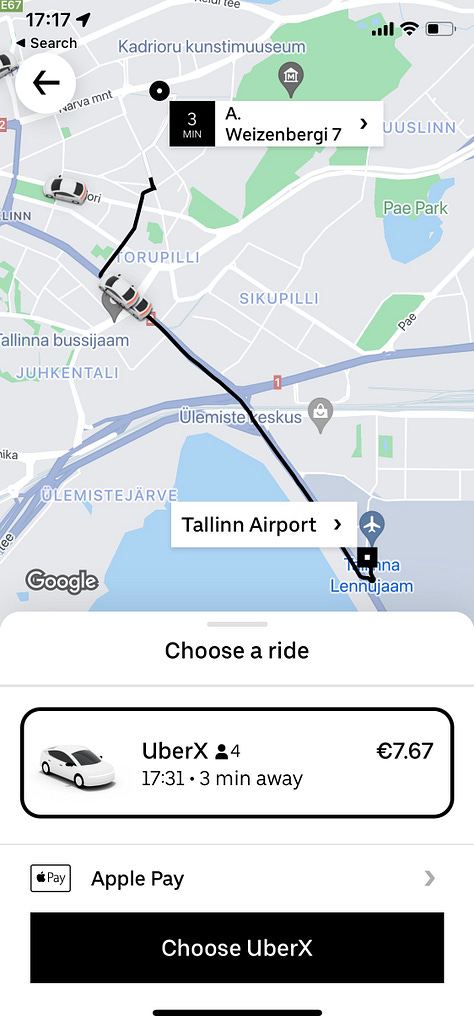

The way people pay across the world is different. In some countries, cash is still the king; in some local payment players rule over major platforms (e.g. PayPal in Germany, BLIK in Poland, UNI in India, etc); while in some, the basic card transactions with GooglePay/ApplePay are the most popular methods of payment. Moreover, since payment is practically the most sensitive step in the whole user journey, the level of trust (or readiness to give money) would depend on the maturity of the market.

Awareness

Services reach different countries at a different paces. E.g. 15 minute dark store delivery might be a well-established practice in Berlin, while a relative novelty for some Southern European countries. With awareness comes the speed of adoption.

Efficiency of use

As we’ve discussed in the Generational divide, the earlier the user is exposed to new technologies, the more skillful and fast she would be.

Skewed use patterns due to local regulations

There are plenty of local regulations across the world - from outright bans to privacy rights protection. All those force the users to adopt (e.g. notorious “Accept cookies” as a side-effect of the EU GDPR regulation) and leave an imprint on behavior.

However, besides the aforementioned differences, the way users behave and make decisions using apps and web services is shockingly similar. Let’s dissect the key commonalities that shape the usage patterns.