First principles

Customer research can mislead your product in the early stages. First principles are a cheaper and more efficient alternative. A product manager's guide on why, when, and how to use them.

On our recent team event, I’ve watched a keynote from one of our user-facing teams.

They said all the right things: you need to do user research, conduct interviews, and pinpoint specific problems. In order to spice it up, they decided to show a few video snapshots from the actual user calls.

Over the past 4 years, I’ve interviewed ~500 PM candidates and ~99% of them said the same thing: we need to do customer research. It seems that this assumption crept in and became foundational for many. But it’s also very flawed.

Back in 2006, Apple did a 900-user qualitative survey. They asked people whether they wanted to have a device that would combine the functionality of a music player, telephone, and a camera. Around 70% said a strong no. When asked why, most people explained that they would never carry such an ugly and heavy device with them.

For a non-existing or an early-stage product, customer research will have little value. You’ll just collect a bunch of misconceptions or biases. What should you do instead?

Apply first principles thinking. But how?

Today’s article

The basics behind first principles. Explained in an accessible way.

First principles vs. research. When to use and when to avoid them?

Mental models for product managers. Actionable set of first principle axioms (with case studies) applicable for product managers and entrepreneurs that you can start using immediately.

📝 Word count: 1190 words

⏱️ Reading time: ~8 minutes

🌟 The basics behind first principles

As Shane Parrish puts it, “First principles is a way to separate underlying ideas or facts from any assumptions based on them”. What remains are the essentials.

Essentials are foundational knowledge that doesn’t change.

In other words, you drill the problem down so deep that what you’re left with is a non-reducible element (for instance, cost).

This element should be phrased as a statement of falsifiable fact and NOT an assumption.

For instance, “customers are going to love my AI product” is an assumption. On the other hand, the value proposition statement like “customers are making a choice based on time savings and price” is a falsifiable fact.

Once we have figured out the fundamental truth, we could reason up from there.

Seems intuitive, right? Why aren’t more product managers using this?

Mostly for two reasons. First, it’s a cognitively demanding exercise. Hence, they choose a path of the least resistance and stick to the known methods (e.g., customer/problem/solution). Secondly, in most cases it’s unclear what this non-reducible element should be.

In physics you have basic laws, in math you have axioms. How do you figure it out for business and product management?

In the last chapter, I’ll give you an exhaustive list of such elements (with a downloadable template) that you can start applying in your everyday work immediately.

📈 First principles vs. research

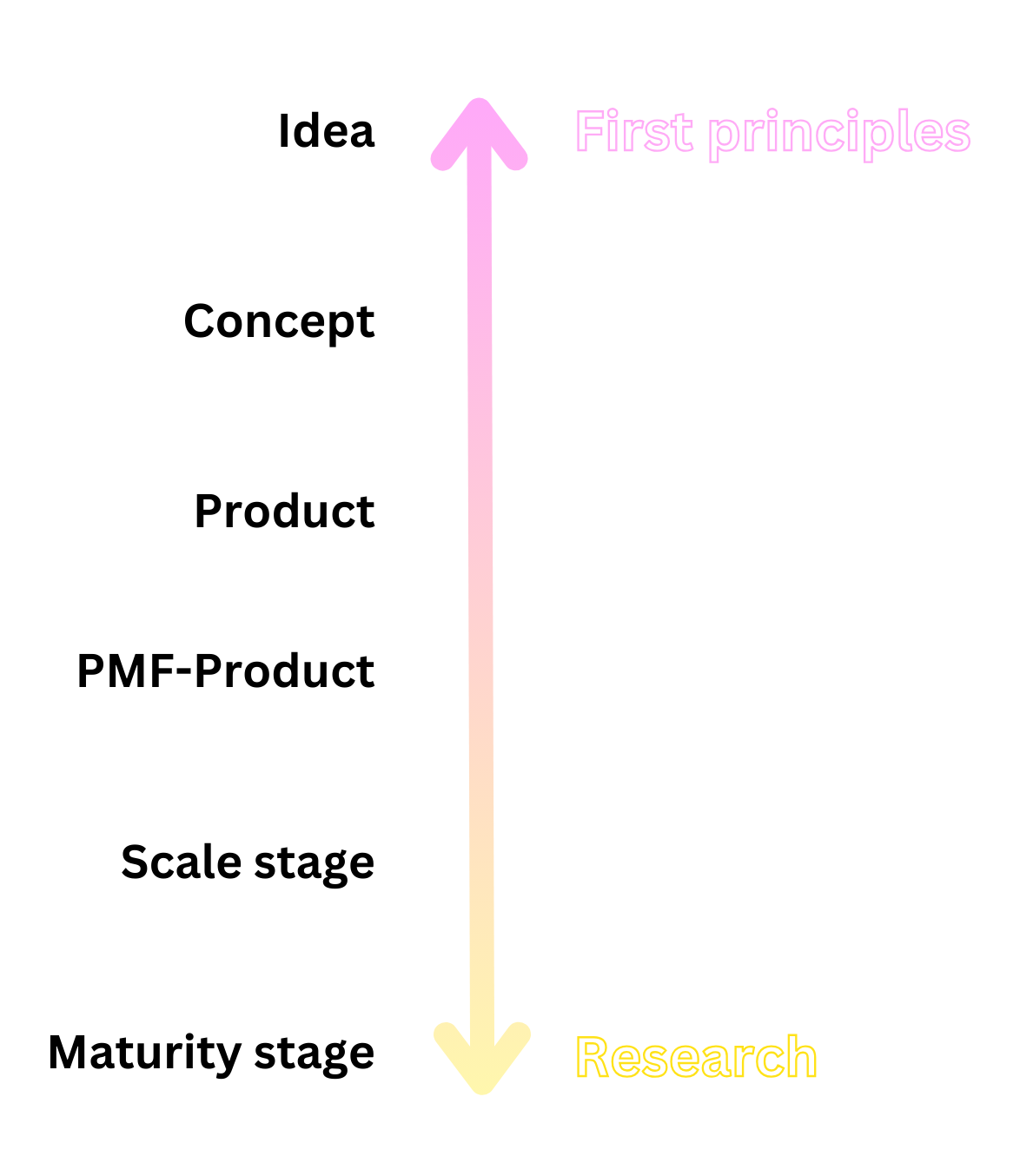

When do you apply first principles or switch to research?