Five Deadly Sins of Org Design

The ultimate no-bs guide to organizational design. Key pitfalls to avoid when shaping your product organization.

I’ve always found the field of Org Design to be theoretically vague - and it’s no surprise. Most of the books on the topic are not actionable.

Authors like Naomi Stanford or Jay R. Galbraith come from academia and fog the reader with dense musings on the types of org structures.

Frederic Laloux and Henry Mitzberg romanticize innovative models, like self-managing Teal organizations “with an evolutionary purpose”.

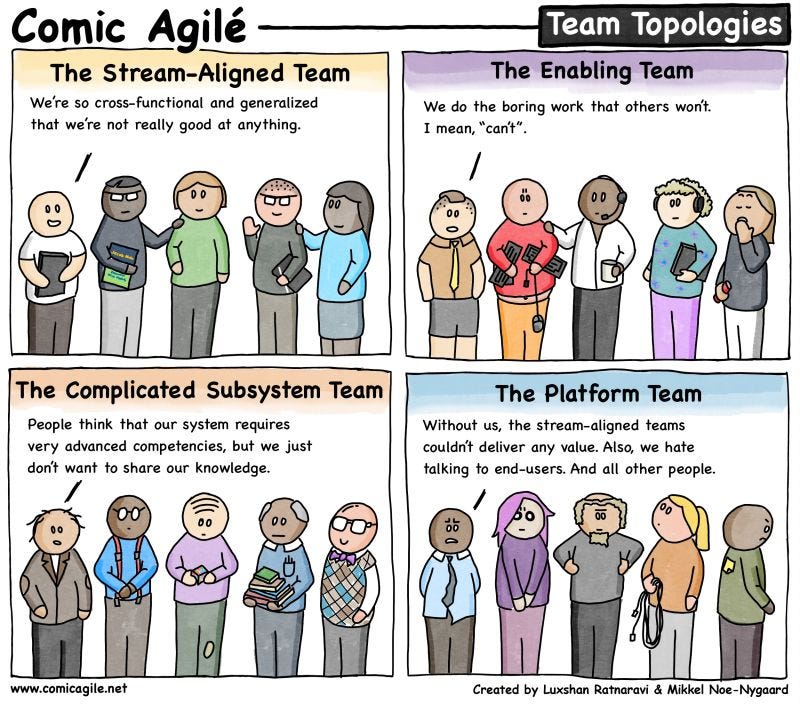

The only truly actionable book is Team Topologies. Concepts like Conway’s Law (aka your product is a consequence of your org design) and Lasagna teams (Stream, Platform, Service, and Complex Structures) have become parts of the basic leadership toolkit.

But org design presents far more challenges than these books address. In my experience, the best insights come from seasoned practitioners - leaders with real experience in building teams.

This article aims to cut through the theory and explain what works, what doesn’t, and why - in the most practical and concise way possible. No academic fluff.

Today’s article

Quick Primer on the Org Structures. Types of org structures. Management types. Tribes versus domains.

Core principles. Clarity of the goal. Manageable scope. Information scope. Non-rigid structures.

🔒 Five deadly sins of Org design. Structures for people instead of business. Output metric goals. Too many juniors. Hiring people for projects instead of strategy. Duplicating centers of expertise.

🏗️ Quick primer on org structures

Types of org structures

There are only a few fundamental organizational types.

A company can be flat (one leader, multiple direct reports) or structured into entities like functions or divisions (e.g., verticals). A flat structure works for small teams but becomes a bottleneck at scale.

Other structures may seem “theoretically plausible” but don’t work in practice at scale - like matrix organizations, where employees report to multiple bosses.

Unless an organization is highly mature, this “multiple bosses” approach will quickly escalate into confusion, conflict, and inefficiency.

Teams can also be embedded within other functions. For example, at Bolt, the Data Science team was embedded in Engineering, while at Umico, the Product Design team was embedded in Product.

This approach depends on your strategy: does the team function as an impact lever (a standalone branch) or as a service layer (an embedded team)?

Management types

At large scale, only one approach truly works: hierarchy. A top-down leader (CEO) has direct reports, and the structure cascades down the organization.

Concepts like Holacracy and self-governing teams may be intellectually stimulating, but they are rarely practical at scale. In most cases, self-governing teams end up in siloed groups of people doing low-impact local optimization.

Zappos notorious experiment on Holacracy is a great illustration to it.

Tribes and Squads VS. Domains and Sub-domains

I once tried calling my teams “domains” and “sub-domains”, but it only led to frustration from my direct reports.

What is a domain? What’s a subdomain? How big can they be? How many subdomains fit in a domain? What’s the difference between a vertical and a domain? The questions never stopped.

Now, I prefer tribes and squads - a simple, elegant model with clear rules. Of course, it’s not a silver bullet and shouldn’t be applied rigidly.

A tribe is a group of squads, typically 2 to 6 squads (fewer squads will lack scope, more will create confusion). A squad consists of 5 to 10 people, give or take. That’s it.

🎯 What’s important

A few core things are truly important; the rest is merely academic dabbling.

✅ Clarity of the goal

Each team, at the most granular level (squad), must have a clear, standalone goal.

This goal should not only be well-defined but also explicitly linked to a higher-level business metric. The team should have a crystal clear understanding of how their input goal moves the needle for the output metric (e.g. GMV/Revenue or EBITDA).

✅ Manageable scope

The clearer the boundaries of ownership, the easier it is for the team to operate and align with other teams.

Manageable scope is typically an end-to-end product, part of the funnel or a service (if the product is more complex).

Figuring out the boundaries of scope is tricky. If you make a scope too large and not have the maturity in the team, you can set it up for failure.

One good example is “here’s the business, think about it, but maybe it’s not the right business and we should be building something else entirely”. Team might jump around between optimizing the existing product and market analysis, eventually ending up with zero output in both directions.

✅ Information flow

Teams need to interact and exchange information freely. When organizational design is a mess and teams are siloed, the flow of information comes to a halt.

Any “us vs. them” dynamics can lead to information being withheld. For example, when teams have overlapping goals, they may start working against each other. This, in turn, can result in duplicate efforts, multiple centers of expertise, and overall slower progress.

✅ Non-rigid structures

A rigid structure is the one that cannot scale or re-shuffle if needed.

Think of an org design as a gardening exercise. Each year you have to tend to your garden and cut out the weeds, replant some flowers into bigger pots and get rid of the others. If that doesn’t happen you’ll end up with an overgrown mess of a garden.

With the introduction of a new annual business strategy, org design should change as well. Impactful teams need to be scaled (e.g. you might be adding new verticals to your business and each will require a separate product team), less-impactful ones reshuffled into higher-ROI activities.

When a team is rigid it will resist all of those changes. Instead of doing the change managemenent, you’ll be dealing with damage control and personal dramas.

Three reasons why teams can become rigid are - overly complex hierarchical structures with multiple layers of reporting, siloes and lack of psychological safety. Yes, fear-driven bosses can make the organizational structures overly rigid. Teams would be fighting for psychological security first and business impact the latest.